Definition

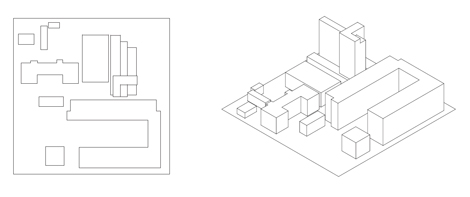

What are creative clusters? Are they “building clusters” or “people clusters”? How to define creative clusters seems to be the fundamental question at the beginning of this research. According to UNESCO (2006), creative clusters are the geographic concentration which “pool together resources into networks and partnerships to cross-stimulate activities, boost creativity and realise economies of scale.” This definition reveals the components that form the notion of creative clusters. First of all, the “geographic concentration” means proximity in which people can meet, interact and inspire each other. Secondly, networks and partnerships are crucial to build a vibrant vision for clusters. Furthermore, a creative cluster is eligible to produce creativity. Finally, clusters have economic implications that contribute to the overall creative economy.

The above definition paints an idealised image for creative clusters. It echoes Landry’s vision (2000: 133) of “creative milieu”, which is “a place – either a cluster of buildings, a part of a city as a whole or a region – that contains the necessary preconditions in terms of ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ infrastructure to generate a flow of ideas and inventions. Such a milieu is a physical setting where a critical mass of entrepreneurs, intellectuals, social activists, artists, administrators, power brokers or students can operate in an open-minded, cosmopolitan context and where face to face interaction creates new ideas, artefacts, products, services and institutions and as a consequence contributes to economic success.”

The question however is whether those elements always coexist in a creative cluster. This is the central inquiry during the course of examination. This review will further explore the notion of creative clusters by looking at the theoretical aspects of recent debates. The aim is to develop ideas and parameters for clusters, rather than to prove a fixed definition in a determinate way.

Economic or Culture

Creative clusters without doubt have a significant contribution to local economy. The geographic concentration and proximity provides economic advantages ranging from agglomeration of creative knowledge and skills, shared resources and mutual help among other benefits. (Evans 2009; O’Connor 2007) To some extent the economic benefits make the creative economy comparable to other industries, and position it positively in the economic system. However, it is always difficult to combine “culture” and “economics” within cultural policy making (O’Connor & Gu 2010). In many cases, the success of creative clusters is not simply measured by economic profits.

The value of creative clusters far exceeds measureable quantities. Bell and Jayne (c2004) show the concern that the pursuit of capitalism and economic growth without considering “social justice” in contemporary urban development may cause a severe social and spatial segregation. Landry (2000: 60) also points out that “financial capital becomes only one asset among many, including human, social, physical, natural and cultural capital”. Significantly, creative clusters can promote creativity and contain sociocultural meanings.

The difficulty of combining culture and economic factors is demonstrated in the process of gentrification, which entangles cultural industries in a ubiquitous development cycle. Artists moved into the areas of cheap rent first, and then the Middle class or developers replace them by bohemian residences. This is seen in Zukin’s “Loft Living”. In the book, Zukin (1982) depicts a more complicated relationship between art and real estate markets by “showing a process of consumption-based ‘landscaping’” (O’Connor & Gu 2010). As O’Connor (2007:35) describes, “the story of how artists in Soho won their battle against the developers – who wanted to knock down this old industrial area and destroy the lofts which had become home to many of New York’s leading artists – only then to lose it again as rental and property values went sky high, is well known.” He later concludes that although gentrification is “often intoned than actually examined”, two facts are rather obvious. First, “culture”, often perceived as “cool” and bohemian characters in urban environment, always adds value to urban real estate. In a sense, it triggers culture-led urban regeneration. Second, “the urbanity of city life”, partly driven by commercial activities, actually facilitate cultural activities.

Bottom-up or Top-down

A spontaneous or planned approach to forming creative clusters stirs debate. Historically, creative clusters developed informally (as also mentioned above in gentrification): artists find the cheap space to set up studios (Butt 2008). In the last ten years, the clusters have shifted from a spontaneous and organic evolution to a planned process, mostly driven by political agendas for economic and cultural prosperity. However, in many of these “planned” districts, often described as “dead doughnut”, has nothing creative been produced, except driving up local real estate prices (Porter & Barber 2007; Rossiter 2008). Therefore, Butt (2008) argues, “manufacturing a successful creative sector from scratch is an almost impossible process – creativity is not generated, it emerges.” The advocacy for bottom-up activities can be also seen in other literature on cultural planning and creative quarters. Westbury (2008) points out, “there is no easy way to buy or build a culture. Culture has properties that defy planning. The more you grab at it, freeze it and attempt to set it in its place, the weaker it becomes.”

Although the organic growth of clustering appears to be more favoured than a rigid planning process, Porter and Barber (2007) argue that either “hands-off” or “hands-on” approach has their disadvantages, for instance, driving up real estate prices that leads to exclude artist community. By using many European examples, such as Manchester’s Northern Quarter, Sheffield’s Creative Industries Quarter (CIQ) and the Temple Bar, they claim that “non-intervention may be no longer an option”. Thus the question is actually what the appropriate ways to manage the creative clusters are or what sort of intervention can help foster successful creative clusters.

This is not an easy question to answer. Two things at least are clearly stated in many cases. First, the establishment of a partnership between public and private sectors and an association within community groups is required. O’Connor (2007: 52) indicates that “there is a certain naivety in thinking that adequate intelligence can manage a complex creative cluster. In fact this only works if a certain set of values are being shared.” Second, “soft planning” emerges as “more diffused, fragmented, and flexible modes of governance” (Porter and Barber 2007). Recently Arts NSW has launched an Empty Spaces program (http://emptyspaces.culturemap.org.au/) which is an example signifying the shift from traditional governing structures to responsive and community-based organisations.

Production or Consumption

To transform the city into a hustle and bustle area has been the main goal in urban regeneration policies. The new urban life is partly (or in large part?) formed by consumption activities, including cafes, restaurants, bars and some cultural venues, which enhance the perception of vividness and vibrancy. In his book “The rise of the Creative Class”, Florida (2003) describes the magnet for creative professions coming to a city is the quality of life, or a sort of diverse and consumption-based lifestyle. He further explores this lifestyle by using the term “Street Level Culture” which includes a “teeming blend of cafes, sidewalk musicians, and small galleries and bistros, where it is hard to draw the line between participant and observer, or between creativity and its creators” (Florida 2003:166). Currid and Williams (2009) emphasise the significance of the “social milieu”, “the geographical concentration of social networks” to creative industries. In their collaborative project “The Geography of Buzz”, they mapped over 6,000 events in New York and Los Angeles in order to prove the importance of cultural consumption patterns in the cities.

However, this consumption-dominated interpretation of creative industries is widely questioned within and outside academic circles. Scott (2000) provides insight into “cultural products” and their interwoven relationships with “the cultural geography of place”. In some ways, he is “concerned with cultural production rather than consumption” (O’Connor 2007:39). In his imagination “Re-industrial City”, Hill (2010) advocates that some light manufacturing industries, such as “rapid prototyping, 3D printing and various local clean energy sources”, would return to the city in near future. “Made in Midtown” project (madeinmidtown.org) illustrates the real engine in New York’s Garment District is far beyond the glory of flagship stores and runways. It includes a sophisticated production chain that requires many highly skilled specialists including pattern making, sourcing, cutting, sewing, showing, marking, grading and manufacturing.

In fact production and consumption is not irrespectively detached. Evans (2009) argues that the planning of cultural activities should be spatially located close to the “production chains”. Bell and Jayne (c2004) reveal that the foundation of post-industrial economy is actually the interrelation of economic and cultural production and the spaces where the production and consumption activities occur. Zukin (1998:830) also points out “sociability, urban lifestyles and social identities are not only the result, but also the raw materials of the growth of the symbolic economy”.

Local or Global

O’Connor and Gu (2010:125) argues that although “the creative industries are often presented in terms of ubiquitous creativity and global communications, they are very much rooted in particular places”. They further explain this embeddedness “is also about a reflective engagement with the cultural and social and environmental context of these localities” (O’Connor and Gu 2010:131). From their point of view, creative clusters are something very local and the advantage of clustering effects is an incarnation of “tacit, locally embedded skills and know-how” (O’Connor 2004:132). This coincides with Port and Barber’s (2007) criticism when they saw the disjunction between some urban regeneration projects and local culture. By asking the questions such as “what culture and who is represented”, they try to establish a relation between clusters and local identity, and link creative industries to everyday life. In this regards, the resistance of Florida’s creative class and the defence of indigenous culture can be also seen in the literature. (Evans 2009; Oehmke 2010)

It is clear that “local” is crucial to the development of cultural industries. Nevertheless, the definition of “local” becomes more complex in the context of rapid information exchange and floating urban experience. On the one hand, it contains a place specific aspect. On the other hand, it transcends static traditionalism. The meaning of “local” is largely influenced by an influx of dynamic communication, hybrid culture and dense network. It is understood as “social relations” by Zukin (1998). She thinks that although the globalisation phenomenon, such as supermarkets, office towers and urban enclaves is inevitable, localised “social relations” make the space unique. The “Made in Midtown” project reveals, for instance, fashion is regarded as a symbolised identity that is locally supported by “an interdependent network”, various specialists, accessible storage space, active entrepreneurs, immigrant labour and multicultural designers. Because of this, new comers are able to join the “local” quickly “making New York a fashion start-up capital”.

City or Suburb

Compare to the above topics, the discussion on the city and suburbs is more related to the spatial planning discourse. The decline of manufacturing based economy led to the recession in many European cities. “Rediscovery” or “revitalisation” of the City has become a slogan that aims to transform the post-industrial cities into a society based on the provision of knowledge and innovation since 1980s (O’Connor 2007). Scott (2000) reveals that the aim for a dynamic, interactive and energetic urban life is the key drive to this movement.

At the same time, the promotion of cultural industries acts as one of the catalysts to this process of economic, cultural and social changes. The City tends to be “a primary point of intervention for cultural industry policy in creative city policy making” (O’Connor 2004:131). One of the most successful examples is Charles Landry and the Comedia. In the last 30 years, they have worked cultural consultants on projects such as “cultural venues and quarters, street markets, alternative retail, new forms of public art and signage, urban landscaping, architectural and larger scale regeneration projects, and campaigns such as the ’24 hour city’” (O’Connor 2007:34).

In Australia, a similar experience started first in 1990s, Melbourne after economic recession. The City Council initiated a number of strategic urban policies in order to attract people moving to the City. Two of them are worthwhile to mention. The first one is Postcode 3000 which encourages people to live the Central City Area through the provision of incentives. Second, the endorsement of Grids and Greenery strategy set up a framework for the improvement of streets and public spaces where public life thrives. (Rob Adam’s presentation in the City Edge conference, February 2008) In the mean time, the unique pattern of laneway network provides a lot of “fine grain” spaces, which were affordable for start-up creatives during early 1990s (Allchin 2008).

More recently, “A Revitalised City Centre” is addressed on the top of the list of strategic goals in the Sustainable Sydney 2030 plan (www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/2030). Both physical and nonphysical initiatives were set up including the enhancement of public domain quality, the establishment of small business partnerships and the development of unique retail activities among others. It is still too early to see the impact of this plan on transforming Central Sydney. Nevertheless, some creative businesses, including the Gaffa Gallery and Paper Mill, have received support to relocate their home to the City Centre.

Although many cultural policies focus on the City Centre, “creative suburbs” have also drawn attention recently. In the countries where suburban population comprises largely of the total metropolitan population, it is necessary to look at how creative infrastructure can be established in suburbs. Brennan-Horley (2010) demonstrates his findings in Darwin where the interconnection between the City and outer suburbs is distinct by using the integrated methods of “qualitative interviews and mental maps”.

Conclusion

From what I’ve discussed above, the notion of creative clusters is very fluid. It is comprised of a number of parameters around the issues such as economic, culture, top down or bottom up governance, production, consumption, local or global identity, geography locations (city or suburb) and others which I have not included here. To some extent, the assemblage of those parameters conceptually draws an outline for a creative cluster which varies in different situations. Despite the difficulty of precisely defining it, a few principles are distilled from the previous discussion. First, to clarify what potential role the clusters have in relation to the wider creative topology of the city is important to understand their performance. Second, the comprehension of local context including history, culture, demography, planning regulations and so on, is the precondition of examining the clusters in specific cases. Third, without critical analysis, the risk of having an idealised model or utopian vision for creative clusters may cause a homogeneous formulation or the repetition of stereotypes. Lastly, the idea of creative clusters as the “interface” – spatially, culturally, socially and symbolically – emerges to produce creative networks, cultural congregation, meanings and memories. These four principles will guide the investigation of creative clusters in the following steps.

Bibliography

Allchin, C. (2008) The fine grain: revitalising Sydney’s lanes, Sydney: City of Sydney, available at http://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/

Bell, D. & Jayne, M. ed. (c2004) City of quarters: urban villages in the contemporary city, Ashgate : Aldershot, England

Brennan-Horley, C. (2010) ‘Multiple Work Site and City-wide Networks: a topological approach to understanding creative work’, Australian Geographer, Vol. 41, No. 1, pp. 39-56, March 2010

Butt, D. (2008) ‘Can You Manufacture a Creative Cluster?’, Urban China, Special Issue, Creative China: Counter-mapping the Creative Industries, Vol.33

Currid, E. & Williams, S. (2009) ‘The Geography of Buzz: Art, and the Social Milieu in Los Angeles and New York’, www.learcenter.org/pdf/CurridWilliamsGeogBuzz.pdf

Evans, G. (2009) ‘From cultural quarters to creative clusters: creative spaces in the new city economy’, in The sustainability and development of cultural quarters: international perspectives, eds Legner, M., Stockholm: Institute of Urban History

Florida, R. (2003) The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life, Melbourne: Pluto Press Australia

Hill, D. (2010) ‘14 Cities: Re-industrial City’, City of Sound, http://www.cityofsound.com/blog/2010/04/14-cities-reindustrial-city.html

Landry, C. (2000) The Creative City: A Toolkit for Urban Innovators, London: Earthscan

O’Connor, J. (2004) “‘A Special Kind of City Knowledge’: Innovative Cluster, Tacit Knowledge and the ‘Creative City’”, Media International Australia, special issues on Creative Networks, No. 112, pp.131-149

O’Connor, J. (2007) The cultural and creative industries: a review of the literature, London: Arts Council England

O’Connor, J. and Gu, X. (2010) ‘Developing a Creative Cluster in a Postindustrial City: CIDS and Manchester’, The Information Society, 26: 2, 124-136

Oehmke, P. (2010) ‘Squatters Take on the Creative Class: Who Has the Right to Shape the City?’, Spiegel Online, http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/0,1518,670600,00.html

Porter, L. & Barber, A. (2007) ‘Planning the Cultural Quarter in Birmingham’s Eastside’, European Planning studies, Vol. 15, No. 10, November 2007, pp. 1327-1348

Rossiter, N. (2008) Introduction to Section2: Information Geographies vs. Creative Clusters, Urban China, Special Issue, Creative China: Counter-mapping the Creative Industries, Vol.33

Scott, A. J. (2000) The Cultural Economy of Cities: Essays on the Geography of Image-Producing industries, London: Sage

UNESCO (2006) ‘What are Creative Clusters?’, http://portal.unesco.org/culture/en/ev.php-URL_ID=29032&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html

Westbury, M (2008) ‘Fluid cities create’, Griffith Review Edition 20: Cities on the Edge

Zukin, S. (1982) Loft Living: Cultural and Capital in Urban Change, London: The Work Foundation

Zukin, S. (1998) ‘Urban lifestyle: Diversity and standardisation in spaces of consumption’, Urban Studies, Vol. 35 (8), pp. 825-839